It is interesting to see the vacuum that can be created with the loss of a charismatic leader and the way a brand can founder without its founder at the helm. You wouldn’t think that would happen so frequently–after all, most of the brands successful enough that you’ve heard of their founder are built on solid organizations of people who know perfectly well how to manage the business. Dave Thomas, for example, wasn’t really running Wendy’s at the time of his passing, and yet the problems that ultimately led to the sale of the company began to show almost immediately in brand communications once he was gone. So what’s going on? Why and how does the founder’s absence make a difference?

In our work on brands and brand characters, we’ve observed that a charismatic founder often serves as the Storyteller-in-Chief, the one who provides the emotional center of a brand. Often, a strong founder is like the author of the brand story, and as is often the case with authors, the founder embodies the story intuitively because he or she is personally torn by the same conflict that powers the story of the brand.

Wait. What’s that? Conflict?

Every great story is powered by conflict. Once the conflict is over, so is the story. The audience connects to the story through the conflict, by recognizing themselves in the struggle and by identifying with the fundamental truth about the human condition that the struggle reveals. Most great brands are powered in a similar way, by a fundamental human conflict that connects them to their audience and generates a sense of meaning much larger than the rational transaction that takes place. It is that dimension of meaning that elevates great brands above the crowd.

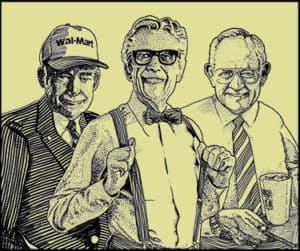

Charismatic founders are often deeply conflicted, which is what makes them dynamic individuals capable of powering successful brands and infusing those brands with story and purpose. Take Orville Redenbacher, the most extraordinary ordinary guy on earth. And that’s a conflict–between the ordinary and the extraordinary–a conflict deeply connected to the magic of popcorn. Popcorn starts as this boring, dried-up little kernel and then explodes into this big, savory, surprising delight. Orville’s fanatic passion for popcorn made him oddly entertaining to watch and infused his brand with its idiosyncratic purpose–to open people’s eyes to the wonder of popcorn. But like Orville, most founders don’t understand how story works. Few are consciously aware of the conflicts that drive them or have much idea how those conflicts impact their businesses. They hold the meaning of the story on an intuitive level, navigating decisions by gut instinct. Such founders make little conscious effort to pass the story along, leaving those who come after with an excellent mechanical blueprint of how the company works but little connection to the emotional juice that makes it resonate with people.

It is easy to believe that this juice is ethereal stuff, purely the province of instinct and intuition. But those who work in story understand that this is not the case. There are elements upon which every great story is founded. These elements can be articulated. In fact, with ongoing storytelling, as in episodic television, they must be articulated in order to ensure that future storytelling connects with the audience regardless of who is actively telling the story or how events specifically unfold.

Wal-Mart is an interesting example. Sam Walton was deeply torn between his desire to win and his desire to serve. He didn’t articulate that conflict for the organization, and he didn’t specifically point out the fundamental human truth that winning is only meaningful when it serves a higher purpose, but he acted within the context of that story by ruthlessly trouncing his competition in service to his customers. After he was gone, the leadership of Wal-Mart focused on imitating his tactics, while the service energy gradually eroded from the brand. The result was that the brand evolved from a servant-leader into a dangerous bully, a transition so complete that it is taking them years to correct their course now that they are turning their focus from Sam’s tactics back to his story.

It is the meaning a founder represents that is engaging. With this in mind, it is at least as important that a founder work to articulate the conflict, meaning and purpose of a brand before leaving it as that he cover the rational, mechanical bases of how the company operates. At the end of the day, the mechanics are the easy part. It’s holding true to the meaning that will continue to attract people to the brand and ultimately keep it off the rocks.